Back again with Taylor Goldberg (@TheHypermobileChiro) to continue the discussion on hypermobility. Our recent blog and instagram post stirred up a lot of conversations that are really important to have in the hypermobility/EDS community.

Comments included strong opinions such from “ALL hypermobility is a health concern” to “everyone thinks they have EDS now because it’s trendy”. We recognize that this community has undergone a lot of medical neglect, trauma, and gaslighting and that these conversations can be sensitive topics - especially for those who may still be struggling with even receiving a proper diagnosis. We hope that we can provide more context and clarity with the next few posts, and share some interesting research and resources.

To clarify, our original post aimed to address how clinicians and researchers are discussing hypermobility on social media. We recognize that the clinical setting is very different, but it’s important to remember that Instagram is not a clinical environment, and we must all keep this in mind when sharing information with a broad audience.

Generalized Joint Hypermobility and CTDs

Generalized joint hypermobility (GJH) refers to an increased range of motion in the joints, body beyond the “normal” limits. People with GJH can move their joints more freely and to a greater extent than the average population, which may be referred to as being “double jointed”. This is not the same thing as flexibility.

GJH can occur without causing any symptoms or it be part of a connective tissue disorder, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), hypermobility spectrum disorders (HSD) and other connective tissue disorders (CTDs). In some cases, GJH is associated with pain, joint instability, and an increased risk of dislocations or sprains. It can also be associated with systemic issues that impact more than just the musculoskeletal system.

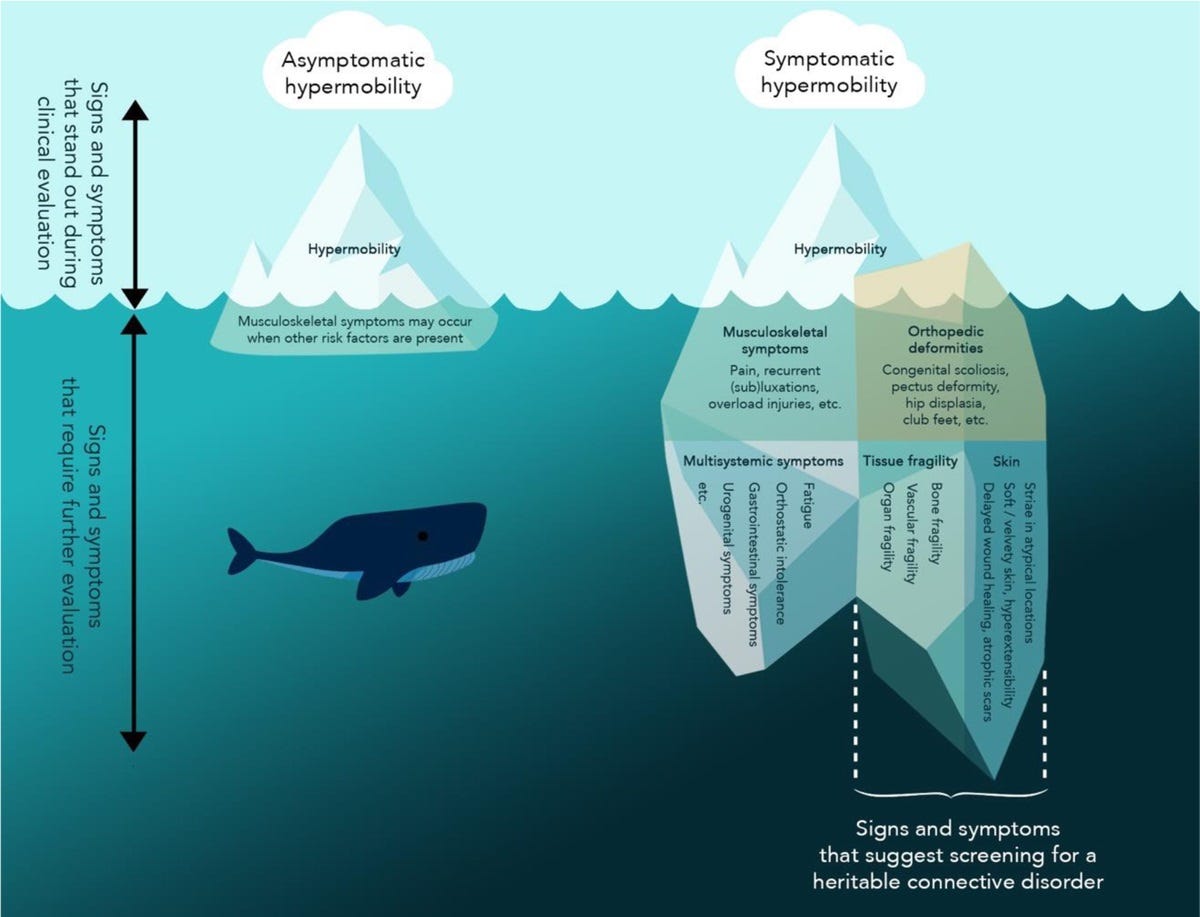

Symptomatic vs Asymptomatic Joint Hypermobility

While it can cause issues, joint hypermobility can be completely normal trait without health consequences, this is referred to as asymptomatic joint hypermobility. However, in some cases, hypermobility that is asymptomatic may become symptomatic later - that means that some people who fall in the “normal trait” category might not say there. This is why connective tissue disorders, especially Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS) have clinical criteria that go beyond just joint hypermobility when it comes to being diagnosed.

We hope to clarify that not all cases of hypermobility indicate someone has a connective tissue disorder - as this assumption can be harmful. (and yes, the opposite is also true you can have a CTD without hypermobility too).

So, for many in the EDS community, the question arises of “how do we even know that asymptomatic hypermobility exists?” Well, it’s been well documented in research for a long time. Let’s break it down by some different factors.

Age, Sex and Ethnicity Influence Hypermobility

A large systematic review reported the prevalence of GJH in different ethnic groups to range between 9.4% and 36%. The same study also found that younger children were more hypermobile, and most studies reported a higher incidence of hypermobility in females. Another study on children found that 27.3% had a Beighton score of ≥7/9 and 72% with a Beighton score of ≥4/9, with a decrease in hypermobility with age. Similarly, they found that girls were more hypermobile than boys. 94.1% of the children reported no pain and there was no relationship found between pain and degree of hypermobility. An older study in West African adults found that with a Beighton score of 4/9 or greater as a cutoff, 43% of a rural Yoruba Nigerian population was hypermobile but this hypermobility was not associated with pain.

It is important to mention one limitation - that most studies focused on pain in reference to “symptomatic”, so it is not known what other health factors may have been relevant in these studies. Additionally, as they were not longitudinal studies, there is no information on participants developing symptoms later in life.

Remaining Questions

So where does this leave us? We know that 1/3 of the population certainly doesn't have a connective tissue disorder. There are many examples of healthy, talented athletes and musicians with hypermobility that seem to have advantages in their fields. So when does hypermobility become a problem? and why?

At what point do we attribute things as being due to hypermobility vs associated with?

We know that more hypermobility does not = more health issues, consequences or comorbidities. So, are we focusing on the wrong thing?

Scientifically, it’s fascinating that there appear to be three groups that people with hypermobility fit into:

Those with hypermobility and no health issues

Those with hypermobility and various symptoms and comorbidities for as long as they can remember

Those with hypermobility who become symptomatic later in life, often after a “triggering event” which could be an injury, accident, infection, puberty or other hormonal change

(Keep in mind, these groups aren’t necessarily based on published data, but something that is broadly observed in this field.)

What’s going on genetically and biologically that makes groups 2 and 3 different? Are there ways to prevent the “onset” in group 3? We certainly don’t have these answers yet, but I hope future research will start to shed light on this.

A great publication for more reading can be found here. The authors visualization of hypermobility does a great job of summing up this topic.

I’m kind of wondering about the impact of life experiences on asymptomatic generalised hypermobility ? I was not diagnosed until mid 40s after serving in military, working in healthcare and 2 pregnancies now I have an HSD / hEDS diagnosis and seems to me like if I’d understood my hypermobility earlier in life I could have made different decisions that might have led to better outcomes for my health. I’m meeting other veterans who are also struggling physically a lot after military training and service.

Soy de Argentina, Buenos Aires. Hace unas semanas la Reumatologa junto con la Kinesiologa ,me dijeron que que mi nena de 6 años tiene Síndrome de Hiperlaxitud Artícular. Ella tiene muchos síntomas,desde dolores de cabeza,articulaciones, musculares, mareos, reflujo o dolor de panza,falta de equilibrio y coordinación. Todavía sigue en estudio, pero aquí me dice que los dolores de cabeza no son del Síndrome de la Hiperlaxitud Artícular, pero al escuchar a otros pacientes con lo mismo dice tener migrañas.

Aclaro también que tiene una mala formación en la base del cráneo, que produce una Invaginacion Basilar( Esto salio en una Resonancia magnética de cerebro con contraste), que según el Neurocirujano, no comprime sólo está en contacto con la médula y por eso dice que no debería tener síntomas

Me siento como mamá super perdida....

Es muy difícil, siento que no esta clara la información y en el mientras esperamos ella sufre.

Quizás ustedes me puedan orientar . Desde ya muchísima Gracias!!!