Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes & Disparities in NIH Funding

$47B in NIH funding available for FY23, yet EDS barely receives a penny

The NIH is instrumental in research progress, giving at least $40B in funding each year (with $49B for FY23). This money is awarded through the various Institutes and Centers to successful grant applications. Different Institutes have their own budgets each year and pay lines for grants of different levels according to those budgets. Sometimes, specific initiatives will allow for more money to go toward specific disease areas with significant unmet need. While the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS) don’t necessarily fall under only one NIH Insitute, studies may have somewhat of a benefit in being able to be funded under several different institutes, depending on the project. Given the estimated prevalence of the most common subtype (hEDS) being 1 in 500, and others around 1 in 5,000 or 1 in 10,000, it would almost be expected that there would be a lot of funding going toward EDS research - at least close to that of other diseases with a similar prevalence. But that isn’t the case.

As a postdoctoral scholar, grant funding is an important part of my academic career and will continue to be in the future. Most academic labs are run exclusively off of grants, and the NIH is usually a key funding source for principal investigators. I was recently awarded an NIH fellowship grant, which led me to take a closer look at funding for EDS research and how it compares to other conditions.

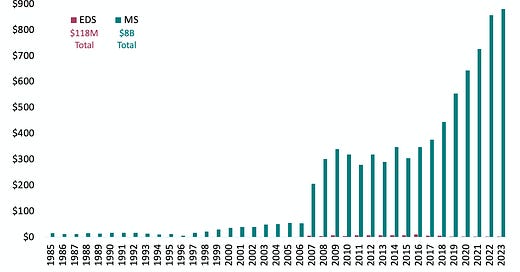

And… the funding disparities are immediately obvious. A mere 15 projects, with a total expenditure of $118 million in the last 38 years, touch upon EDS in some capacity, meaning somewhere in the grant it mentions EDS, but may not be directly focused on it. However, not a single dollar is designated for projects exclusively focused on hEDS (but I can proudly say my fellowship, although not a faculty-level grant, is changing that).

So, let’s contrast this with other connective tissue disorders. Marfan syndrome, with a prevalence of 1 in 5,000 has acquired $289 million in funding, supporting 778 projects. Even more staggering is the funding allocated to conditions like Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and Lupus—$8 billion and $6 billion, respectively—fueling over 19,000 and 16,000 projects each despite the fact that these conditions impact even fewer people than hEDS.

This disparity isn't only a financial shortage; it reflects the impact on patient care and scientific advancement. Conditions with robust funding streams have witnessed transformative developments. Marfan syndrome, benefiting from substantial investment, boasts advanced diagnostic tools, clinical guidelines, effective resources, and evolving treatment options. Similarly, diseases like MS and Lupus have seen remarkable progress in understanding disease mechanisms, leading to targeted therapies and improved patient outcomes.

The lack of funding dedicated specifically to EDS translates into limited research initiatives, few researchers working on these conditions, little advancement in diagnostic tools, and inadequate treatment options. The impact of NIH funding on research cannot be overstated. Beyond the financial aspect, it shapes awareness, fosters collaborations, and fuels scientific breakthroughs. The need for increased NIH funding for EDS research is urgent. If you're passionate about driving change and ensuring that conditions like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome receive the attention they deserve, your voice matters.

Contacting your local and state representatives is a powerful step toward advocating for increased federal funding. Reach out to your senators and congressional representatives, expressing your concerns about the underfunding of EDS research within the NIH. Highlight the impact of increased funding on understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition.

Additionally, engaging with relevant advocacy groups and patient organizations dedicated to EDS can amplify your voice. Joining these groups can offer support, guidance, and collective strength in advocating for policy changes and increased research funding. We are working hard on making change happen in the lab as well, to hear more about our efforts, check out the Norris Lab website. Together, we can urge policymakers to prioritize EDS research within the NIH, ensuring that adequate resources are allocated to further research efforts and improve the lives of those affected.

Disclaimer: These statistics come from NIH Reporter searches (https://report.nih.gov/). Grants awarded multiple years may show up as additional projects. By searching for “Ehlers Danlos Syndrome” or “Multiple Sclerosis,” etc, any grants mentioning these conditions in the abstract will show up. In many cases, these can be studies that mention these diseases as having clinical relevance for the biology they are working on, but are not focused on these diseases directly.

Also, this is not to say that any of these conditions should receive less funding than EDS, as they all warrant research attention. It is just to highlight conditions with a similar prevalence and shortfalls in funding for EDS/hEDS/HSD.

I will be sharing similar funding comparisons on Instagram from dysautonomia/POTS, MCAS, ME/CFS and more conditions.

Once your gene (enzyme) research is published, there will be something to build on. The diagnostic criteria for hEDS also need to be better thought out. Many doctors see them as non-specific; for instance, Mitral Valve Prolapse (MVP) affects approximately three per cent of the population, and women are twice as likely to be diagnosed as men. However, what percentage of women with hEDS have mitral valve prolapse is not known. A percentage often thrown around is that 28%–67% of hEDS patients have MVP, but this nonsense can be traced back to a paper that indicated that 28%–67% of hEDS patients have variable ECG subclinical anomalies, i.e. so not MVP in itself but ECG subclinical anomalies, yet the diagnostic criteria encompasses MVP only and aortic root dilation with Z-score >+2. Aortic root dilation with Z-score >+2 is diagnostic in Marfan Syndrome, not hEDS (if it is diagnostic, where are the studies indicating it is)?

Omitting structural issues such as (occult) tethered cord syndrome as part of the hEDS diagnostic criteria is another mad issue despite Brock et al. (2021) finding a prevalence of 40% of (occult) tethered cord syndrome in hEDS, especially since such structural issues can now be diagnosed with somatosensory evoked potentials, and motor evoked potentials looking at Central Motor Conduction Time (CMCT) and Peripheral Motor Conduction Time (PMCT) see for example; Kamei, N., Nakamae, T., Nakanishi, K., Morisako, T., Harada, T., Maruyama, T., & Adachi, N. (2022). Comparison of the electrophysiological characteristics of tight filum terminale and tethered cord syndrome. Acta neurochirurgica, 164(8), 2235–2242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05298-4

I could go on, but I'll stop.

This is an important post that I'm glad you wrote, Cort!

Given that you've found hEDS is more prevalent in women, I would expect that the broad gap in women's health funding by the NIH and VCs are further exacerbating this disparity.